On April 6, 1994 at around 8:30 p.m., while it was descending on Kigali, the plane carrying Presidents Habyarimana and Ntaryamira was shot down over Kigali. The next day, as the RPF launched a general offensive on Rwanda, the genocide against the Tutsis began in areas controlled by the then government.

On April 7 1994, Mireille Kagabo, then aged twelve, saw her life turned upside down. Her father, Innocent Kagabo, was killed by gendarmes of the Habyarimana regime on the afternoon of 7 April near their family home. He will be among the very first victims of the genocide. Mireille’s carefree life was transformed in the space of a moment into that of an orphan who was hunted down for three months because of her ethnicity and came close to death on several occasions. Twenty-six years later, on the occasion of the “International Day of Reflection on the Genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda in 1994“, Mireille recalls her journey of horror and wonders whether Rwandan society has really embraced the path of the never again.

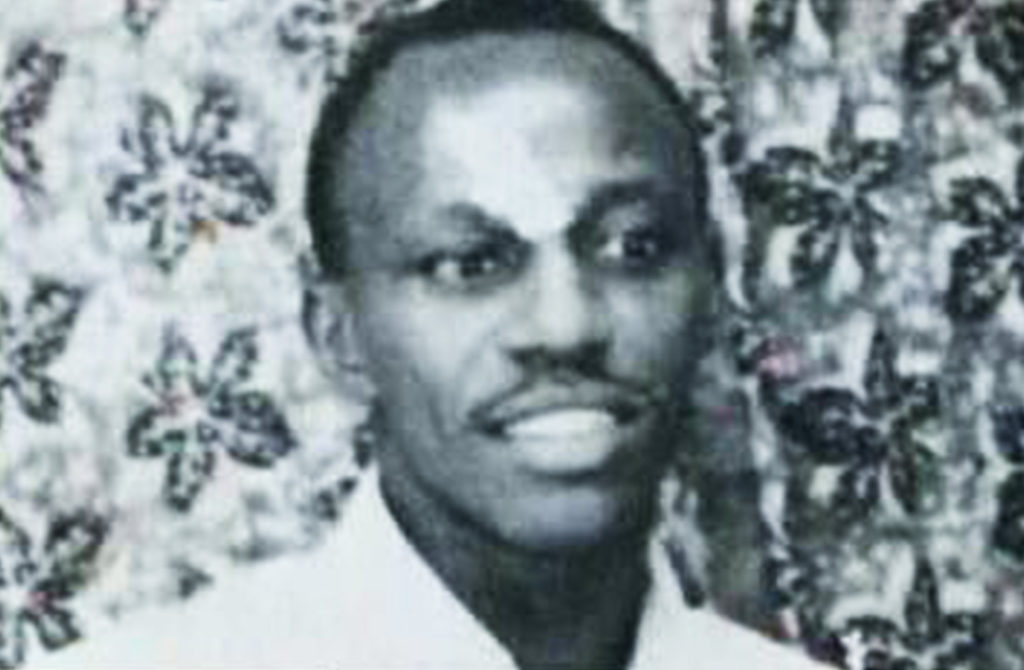

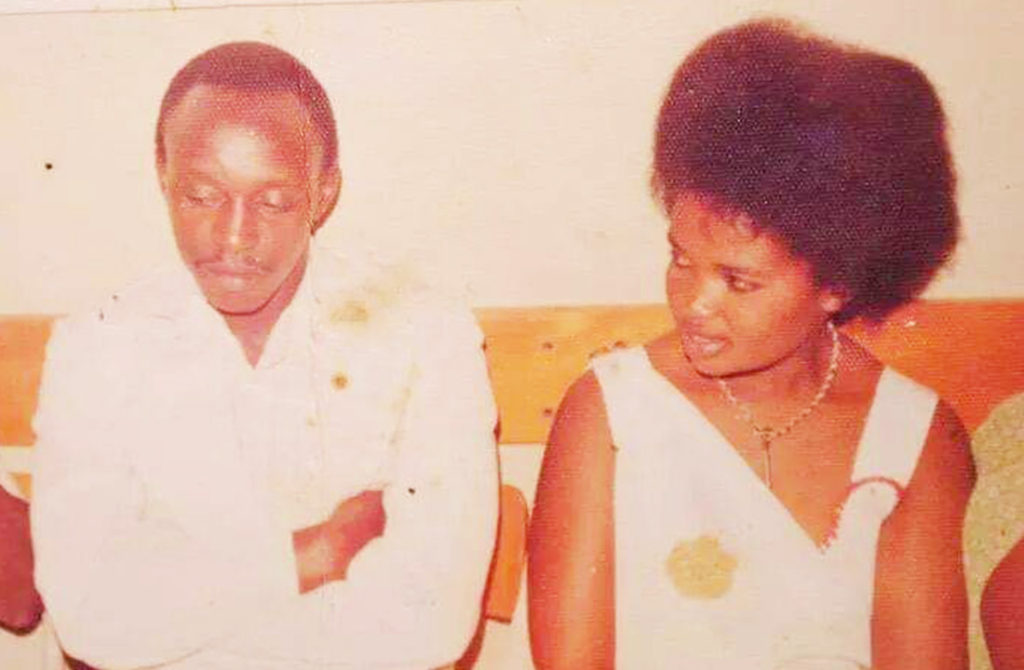

Mireille was born on 29 July 1981 in Kigali, in a family of five children. Her father, Innocent Kagabo, worked at the Ministry of Justice but it was mainly for his soccer talents that he was known, as he was one of the stars of the Kiyovu football club and the Rwandan national football team. Her mother, Eugenie Utamuliza, was an independent businesswoman in Kigali.

Mireille describes a happy childhood far from the ethnic problems that had torn Rwanda apart in the past, and were about to tear it apart again a few years later: “Until I was six, I didn’t know my ethnicity, It was at school that I first heard about ethnicity when the teacher asked the students to stand up according to their ethnicity, when I came home I asked my father which ethnic group I belonged to, that’s the moment I learned that I was Tutsi” Mireille recalls.

From that day on, each time the students were invited to stand up according to their ethnicity, Mireille will be the only one to stand up at the call of students of Tutsi ethnicity “that’s how I learned that I was the only Tutsi student in my class, the following year there were two of us, my cousin and I but that had no consequences on my relations with the other students“.

“I think that as a Tutsi who was critical of the government, he was condemned in advance”

Mireille was 9 years old in October 1990, when the RPF, a politico-military group composed mainly of Tutsi refugees, attacked Rwanda, and the first persecutions quickly affected her family: “My maternal grandfather was imprisoned as an icyitso [accomplice, the name given to those accused of being in connivance with the RPF] …”.

It was difficult for Mireille’s family to accept this news, which they experienced as an injustice: “he was imprisoned on charges of being in collusion with the RPF when he had no link with the movement, I think that as a Tutsi who was critical of the government, he was condemned in advance“.

From that date, the life of Mireille’s family totally changed: “my father was forced to go into hiding several times, he could no longer go out as before and our house was regularly searched. The situation was worse for one of my half-brothers who lived in Burundi and was passing through at that time, he was locked down in the house and had to remain permanently hidden“.

In October 1993, after the assassination of Melchior Ndadaye, the president of neighbouring Burundi of Hutu ethnicity, Mireille’s family even felt compelled to take refuge; “after his assassination, we took fright and went to take refuge in the convent of the Little Sisters of Jesus in Kicuciro. The same scenario happened again in February 1994 after the assassination of Martin Bucyana, nobody told us to flee. It is difficult to know afterwards if our fear was well-founded, but afterwards we always heard that such and such Tutsi family had been killed by people who were taking revenge for these assassinations“.

“My older brother who was going on 15 turned around and saw everything”

On 6 April 1994, Mireille was at the family home with her father, her four brothers and sisters and a cousin who had been adopted by the family, while their mother was in Kenya. “It was only on the morning of 7 April that I learned that President Habyarimana’s plane had been shot down,” tells Mireille. “My cousin was happy about Habyarimana’s death but my father told her not to rejoice, telling her that it wasn’t going to end there, he was afraid, he was scared, he liked to play music and spent his day playing music and singing religious songs on his instrument“.

The father’s fear soon proved to be well-founded when, on the afternoon of 7 April, gendarmes arrived at his home and asked their father, the children and three servants to leave the house “outside, they asked us for our identity cards, my father and the servants gave theirs, but we children didn’t have any.”

There followed an exchange of terror with the soldiers, the last sentence of which Mireille remembers is this admonition d by one of the soldiers to her father: “You dare to give me an identity on which it is marked Tutsi?“.

The children as well as one of the servants were asked to go inside the house “I did not know the ethnicity of the servants, but given the exchange around the identity cards which revolved around ethnicity, I suppose the one released was because he was Hutu“.

No sooner had the children made some steps towards the house the shots rang out, “my older brother who was going on 15 turned around and saw everything“. Inside, the children quickly understood what had just happened: “We were paralyzed, we didn’t even ask ourselves what to do, we were just motionless and silent until more shots broke the silence, the servant came running towards us and shouting, they are coming back, run away, run away.”

It is in those conditions that the five children, aged 14, 12, 9, 4 and 3, left their home, by themselves, to take refuge in the convent of the Little Sisters of Jesus where they had previously taken refuge with their parents. “We arrived on 7 April crying and saying that our father had just been killed, they gave us a room where we stayed the six of us, including my cousin who, after having gone for a while to my grandmother’s, joined us.

As soon as they arrived, Mireille and her brothers and sisters witnessed a massive influx of people coming to seek refuge in the convent “it didn’t stop, every day many people kept arriving and we quickly numbered several hundreds“.

“The child whose head they wanted to blow off in front of us is Mireille”

On April 10, soldiers from the Rwandan Armed Forces (the government army at the time) arrived, and invited all those who had taken refuge in the convent to return home “no one complied and the next day other soldiers, this time accompanied by civilians with machetes, asked us to come out and led us to the middle of the main road”.

On the road, the group of several hundred people were lined up and the children were put aside, while among the adults, Tutsis were separated from Hutu adults on the basis of identity cards. “As soon as they saw a Hutu, they asked him what he was doing there and asked him to leave” says Mireille.

The children were invited to return to the convent while the adults had to stay outside. “33 children were able to return to the convent; we never saw the adults again. Afterwards, we learned that they had all been killed and were thrown into a communal grave nearby“.

Some children, because of their height, suffered the same fate as the adults. “I remember in particular Francine and Mutama, two children from my neighborhood who were about my age. Francine wanted to join us, saying that she was the same age as me even though she was taller, they did not allow her to do so, telling her that it was her size that was going to get her killed.”

During the days that followed, the children lived in a climate of fear. “Soldiers continued to come regularly, and each time it was the same ritual, the sisters begged them not to touch us, they looked at us threateningly, sometimes throwing tear gas at us or saying to the sisters: ‘Rwigema also left at this age, give them to us and we’ll get rid of them.

Mireille’s most vivid memory of this period is May 6, 1994, one month after the day of the assassination of Juvenal Habyarimana. On that day, the soldiers returned, more aggressive than usual, gathered the children in the courtyard and one of them put a gun to Mireille’s head. Sister Domitrie, one of the sisters present that day, tells of this episode: “It was May 6, 1994, they had come to avenge Habyarimana. The child whose head they wanted to blow off in front of us is Mireille, they did it to show us that they were not joking, but in the end, they left because all they wanted was food, and when we gave them money, they left.”

Faced with death, Mireille thought about an extract from the Bible that her mother used to read to her and which echoes the prayer of a man who begged God to give him another fifteen years to live: “My prayer was answered, and exactly fifteen years later, at the age of 27 and a half, I had my first child. I see this as a divine sign of renewal of my vow for another fifteen years.”

The incident of 6 May 1994 showed the sisters that it would not be possible for them to protect the children for a long time and they called an officer of the FAR (Rwandan Armed Forces) to the rescue “several soldiers arrived with armored vehicles, I remember one of them who was called Rukundo, I remember him because he was very kind to us, he took us in his arms and comforted us”.

The children were then taken to another RAF officer “the main thing I remember there is the meal they gave us, for several weeks we had been eating salted porridge every day and when we arrived they cooked for us, there was even meat that I almost couldn’t remember the taste of.”

After the meal, the officer gathered them and told them that he was happy to have the opportunity to save such young children, before briefing them “we will escort you to Kabgayi, you will surely hear a lot of shooting on the road, sometimes it will be our own troops shooting at us, sometimes it will be RPF bullets, and you will have to keep calm. What I can assure you is that no one is going to stop you at the barriers.”

It was in this military convoy that the 33 children arrived in Kabgayi, where an IDP camp had been set up. “There were already a lot of people when we arrived there, we were separated from the sisters and stayed there until the RPF troops arrived.”

“I know how much it hurts to lose a father and I did not want to deprive other children unjustly of theirs”

After the arrival of the RPF troops, the children, whose group had now grown to about a hundred, took the road to Bugesera. “On the road we stopped at a certain Nkamicaniye, where we spent a few days. There were a few adults with us, but they were mainly in charge of our food. Nothing more. Our group looked like a travelling orphanage.”

Arriving in Bugesera, the children remained in an orphanage in Nyamata until early July 1994, when the war and genocide ended following the military victory of the RPF.

They stayed there until the beginning of August 1994 when Mireille’s mother, Eugenie, who for a while was consumed by grief after thinking she had lost her children in addition to her husband, came to get them after finally hearing from them “She took in all the 33 children we had survived with from the convent and brought us back to Kigali. At first, we all stayed with my mother, before the other children were later taken by the sisters to be cared for“.

It was on their return to Kigali that Mireille’s family learned that the few family members who were living in Rwanda at that time had been killed. “The majority of my family was living in Burundi or Kenya when it broke out, and when we returned, we had no one left in Kigali, my paternal grandfather, my maternal grandmother, my uncle Alexis Kayinamura, nicknamed ‘Fiston’, all had been killed“.

It is in this post-war, post-genocide and mourning atmosphere that Mireille’s family started a new life, her mother starting a restaurant. Although the situation in Rwanda seemed stable on the surface, killings continued to take place in the country and Mireille’s family was soon affected again “my first cousin’s husband was Hutu, all he did during the genocide period was to protect my cousin and their children, and when he returned he was killed by the new government.”

Mireille and her mother were greatly affected by her cousin’s fate “Although they were both widows, the treatment they received was totally opposite. My cousin had no support and was instead mocked for marrying a Hutu, which was considered a disgrace.”

As a widow of the genocide, Mireille’s mother was quickly asked to join Avega agahozo, the association of genocide widows “she wanted to integrate my cousin, she was refused on the grounds that her husband was Hutu, that he was an Interahamwe, who was not a victim of the genocide, the tone quickly rose and my mother finally never joined the association.”

“As soon as we arrived in Uganda, we learned of the assassinations of Antoinette Kagaju and Asiel Kabera; my mother’s first cousin, in quick succession.”

Mireille keeps a bad memory of those years that followed the genocide; a bad memory caused on the one hand by memories and traumas “the hardest part was every April, we dug up the bones, we washed them, it rekindled our traumas” and on the other hand by various pressures, particularly those pushing them to accuse innocent people of the crime of genocide “we were asked, for example, to accuse a man who had our father killed. This man was Patrick and Nadine’s father, who was not among the people who came to our house. I know how much it hurts to lose a father and I did not want to unjustly deprive other children of theirs“.

But what most marked Mireille during those post-genocide years was the bad atmosphere that prevailed, especially in the relations between the different ethnic groups: “There was a munyagire [a kind of exclusionary policy based on the principle: my enemy must be your enemy], when people came back from Congo, from Tingi Tingi, everybody was talking about it, everybody was pointing at them as Interahamwe. We heard a lot of misplaced and generalizing remarks about them.”

The year 1998 marked another turning point for Mireille and her family. “Genocide survivors from the Kibuye prefecture, like my mother, began to be targeted by the authorities following the assassination of Victor Bayingana, a businessman from Kibuye, by the new government. His wife, Antoinette Kagaju, was unjustly accused of her husband’s murder and then imprisoned. As my mother was friends with Antoinette, she went to her trial and visited her regularly in prison.”

The following year, tensions between the new government and the survivors of the Kibuye genocide, symbolized by the government’s manoeuvres to politically weaken Joseph Sebarenzi, at the time president of parliament, increased, leading Mireille’s family to exile. “As soon as we arrived in Uganda, we learned of the assassinations of Antoinette Kagaju and Asiel Kabera; my mother’s first cousin, that took place in quick succession.”

In Uganda, the family soon rubbed shoulders with other refugees, including several former RPF soldiers who were planning to write a book about the war years, including the executions of their own troops. Among these soldiers was a certain Abdul Ruzibiza, “although I was relatively young, barely out of my teens, I heard various discussions about the war of conquest waged by the RPF, the attack of 6 April 1994 and many other terrible things about the RPF that I found hard to believe. Even though I already knew people who had been killed, such as Corneille’s family who were our neighbors or Silas, my cousin’s husband, I never realized the magnitude and wondered why all these victims were not commemorated“.

But very quickly, on March 17, 2001, as the family began to rebuild in exile, misfortune knocked at their door again. “My little brother, who was four years old during the genocide, went to school in Kasese and was present when rebels attacked the place from the Congo and kidnapped him, until today we don’t know his fate.”

“If a photo of me at an event organized by Hutus was published, they would ask me questions, it was sad to see.”

Following the brother’s kidnapping, the family was taken care of by UNHCR, which managed to evacuate them to Canada, first to Toronto and then to Edmonton.

In Canada, Mireille was surprised to see the barriers between ethnic groups: “Sometimes Hutus and Tutsis would meet at events, but in everyday life people lived separately, everyone knew who was who, if a photo of me at an event organized by Hutus was published, they would ask me questions, it was sad to see.”

In her new welcoming land, Mireille did not forget her history and quickly joined the association GMK; Genocide memory keepers, in orderto preserve the memory of the genocide against the Tutsis “we organized a commemoration every year, with the objective of telling our stories so that history never forgets what happened in Rwanda between April and July 1994.”

But very quickly, Mireille became disappointed “I was disturbed by some of the comments that were made there, they demonized and stigmatized the Hutu as a whole and I asked them, are we really embracing the path of never again by commemorating in this way? I was told that this helped to alleviate the deep pain that the genocide caused us and they asked me who I was to speak for the Hutu, after that episode I left the association because I felt that we were only accentuating these divisions that led us to the genocide.”

This April 7, 2020, 26 years to the day after the assassination of her father, 26 years to the day after seeing her life turned upside down, Mireille asks Rwandans to show compassion for all the victims who have been swept away by the Rwandan tragedy “we often argue over the qualification of the crimes that have been committed in our country, while for me the most important thing is not what took away a loved one but the pain that accompanies such a loss, as Kizito sang, there is no good death, whether it is a victim of genocide or crimes not qualified as Genocide, the pain caused by the loss of a loved one is the same“.

And in conclusion to our interview, she asks, “If on April 7 of every year I have the right to tell my story and be consoled by the whole world, why shouldn’t my cousins, who also lost their father who was killed like mine was, have the same right?”

Ruhumuza Monyumutwa

Jambonews.net