Guest Contribution by Rudatinya Mbonyumutwa.

All genocides are faced with their negation.

The genocide perpetrated against the Hutus of Rwanda by the RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front) of Paul Kagame, over more than a decade, since early 1991 is no exception to the rule.

Yet denying a proven crime is not only an act of solidarity with the perpetrator but an act of complicity which contributes to the completion of this crime.

The genocide committed against the Hutus has common characteristics with the other genocides but has also its own characteristics.

The same is true of its negation which has commonalities with other genocides, but which is also characterised by unprecedented particularities.

A genocide characterised by impunity

Like other genocides, the genocide against the Hutu people fulfils the main criteria of being the crime of crimes, in the sense that it consists of eliminating people due to who they are. However, among its unique and most troubling characteristics, there is first and foremost the total impunity of its perpetrators.

They came to power in Rwanda 25 years ago and their crimes seem to be unnoticed by foreign nations which is difficult to understand. It seems, blatantly today, that the genocide against the Hutus was the almost obligatory passage of Africa greatest criminal enterprise of the neo-colonialism at the end of the 20thcentury.

The war waged by the RPF against the Republic of Rwanda from October 1st, 1990 had internal political motives that were about contesting the 1959 revolution that emancipated the Hutu majority population.

At the same time, this war had an international motive which was to expand Anglo-Saxon influence in the region and the looting of mineral resources in the Eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for the benefit of Western multinational corporations.

Numerous writings have been published on the topics over the last few years and the only consolation for the victims, while still waiting for justice to be rendered, is to begin to understand what really happened.

Specifically, an alliance was made between those multi-national corporations and the Rwandan members of the then Ugandan Defence Forces. The former offered to provide financial, political and mediatic assistance while the latter did all the work on the ground to enable unlimited exploitation of minerals by those corporations. These resources are essential today for the development and sustainability of technological industries.

On reflection, it is obvious that the military power taken by the RPF in Rwanda and the invasion of former Zaïre, now Democratic Republic of Congo, could only be made possible by a partial extermination of the 85% majority Hutu people in Rwanda if the goal was to put in place military power controlled by people from the Tutsi minority.

Up until now, this is how far community or ‘ethnic’ analytical frames of this conflict stop.

This means that the RPF is a political and military movement that emerged from the Tutsi minority and took power after chasing a power dominated by people from the Hutu majority with the support of the neighbouring Uganda army and their Western supporters.

Yet this was far from being a case of inter-ethnic massacres or a civil war opposing Hutus and Tutsis as some have suggested.

Most of Hutus and Tutsis people were mere victims of a war and crimes orchestrated by political and military driven organizations involved in this conflict such as Kagame’s RPF.

Impunity, therefore, is the first characteristic of this genocide. A genocide that was the result of a neo-colonial deal brokered on field by the Rwandese Patriotic Army whose majority of high-ranking officers were below the age of 25 in 1994. Their victims are now estimated at about 2.5 million souls.

Impunity is such that there remains a form of omerta when it comes to publicly naming the perpetrators of this genocide.

Impunity is the worst thing that can happen after a crime of this nature.

Indeed, impunity enables negation and terrorises the victims while comforting the perpetrators with the idea that they were justified in their deeds, most especially if their crimes served as a pathway to seize power.

A widely documented genocide

The second characteristic of this genocide is precisely the documentation which exist about it and which contrasts with its impunity.

All genocides are documented, and it is impossible to imagine a perfect crime of genocide that would leave no trace or witnesses. Yet, as far as the genocide against the Hutu is concerned, the existing documentation is particularly telling.

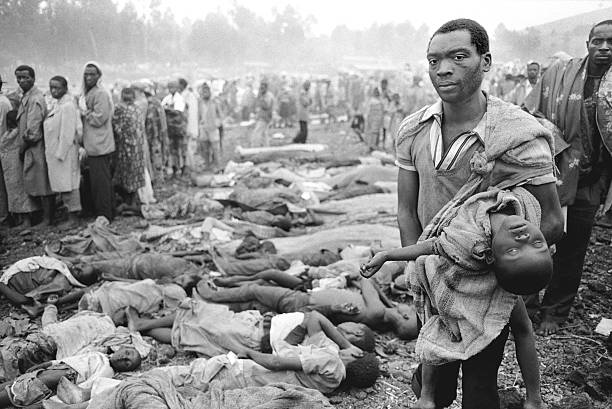

Chronologically, it is the most recent genocide in the history of humanity. It was practically recorded and photographed in real time by satellites. Some rare images that fell into the hands of the public have inspired edifying movies such as ‘‘Tears of the Sun’’ directed by Antoine Fuqua, released in 2003 starring Bruce Willis.

This genocide has been the subject of UN commissioned investigative research, carried out by independent observers as part of their UN official mission. As a reference, we can cite the Mapping Report published in August 2010 by the United Nations.

(https://www.ohchr.org/documents/countries/cd/drc_mapping_report_final_fr.pdf).

The authors of this report are significant in the sense that they include Ms Navanathem Pillay –former President of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and Ms Louise Arbour –former Prosecutor of the ICTR.

On page 589 –paragraph 514 of the mapping report, we can read the following which leaves no doubt as to the nature of the crime:

Characters in bold font here are also bold in the original text.

But there are several other reports including two other previous reports that cannot be ignored. These are those of Robert Gersony of October 19th, 1994 and of Roberto Garreton of April 2nd, 1997.

The Gersony report specifically documented crimes of genocide committed against the Hutus on the territory of Rwanda during and after the RPF’s military conquest; though, the purpose of writing it was to investigate crimes committed from April 1994 with the presumption that all crimes were committed by the interahamwe militias.

This report is therefore particularly important because it is the result of a neutral investigation conducted on the ground between August and September 1994. These investigations were conducted in tens of massacre sites in Rwanda and they were able to collect statements from witnesses who pointed to the RPF as the authors of most killings in those areas.

The Gersony report is certainly no stranger to the neutral and general wording of the UN Security Council Resolution 955 issued on November 8th, 1994. It was this resolution that established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Indeed, UNSC Resolution 955 established an International Tribunal with the mandate to prosecute crimes committed in Rwanda and across the neighbouring territories between January 01st and December 31st, 1994. It does not make any mention as to whom the perpetrators or the victims might be.

It left, therefore, room for the prosecutor to pursue and prosecute all crimes of international criminal law, committed by all authors against all victims. This means that crimes committed by the interahamwe and the RPF were both subject of investigations.

It was only due to political reasons that the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda decided to abort the prosecution of crimes committed by the RPF; a decision which favoured and guaranteed impunity for over 25 years.

However, judicial systems from two different countries have attempted to put an end to this impunity. They did so based on the principle of universal jurisdiction for the prosecution of war crimes, crimes against humanity and crimes of genocide.

Thus, Spanish Judge Fernando Andreu Merelles received complaints from victims’ families and opened investigations. As a result of his investigations of those crimes, he released, in February 2008, 40 arrest warrants against 40 high ranking RPF military officers for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide.

France also commissioned an indirect inquiry into these crimes in the sense that the object of their investigation was the terrorist attack perpetrated against the airplane that killed the French crew transporting Juvénal Habyarimana –former President of Rwanda, Cyprien Ntaryamira –former President of Burundi and other passengers.

Together these investigative efforts have not led to any prosecution yet and they seem to have been hampered by geostrategic and political interests.

A genocide narrated by its perpetrators

Moving now to another distinctiveness of this genocide is that it is narrated, in writings, by some of its executors. Take for instance two of the books produced by RPF soldiers in which one reads dates, sites and other valuable data for the victims.

For the first time, as far as one can recall in history, never before have perpetrators of genocide repented to the point of testifying freely without constraint, in writing in reference works such as is the case in Rwanda. This is seen in the book by Abdul Ruzibiza (Rwanda:Untold story, 2005) or in that of journalist Jacques Pauw (Rat Roads: One Man’s Incredible Journey, 2013). The latter transcribes statements collected directly from a former RPF soldier who revealed his crimes.

The fact that these RPF soldiers testified from their own free will is significant. Otherwise, it would be less credible if such testimonies emerged from alleged perpetrators or inmates or yet again if they were coerced to testify.

With all this documentation that traces a methodical and organized planning and execution, one would think that the justice claimed by the victims would be easily delivered in comparison to what we have witnessed before international criminal tribunals or the international criminal court for other crimes.

In addition, the perpetrators of this genocide belonged to a structured army which claimed to be disciplined in a such a way that there would be no difficulties in identifying those who committed these crimes, though the idea would not be to prosecute low ranking soldiers, some of whom were child soldiers at the time of the events.

In terms of organization, many refugees who escaped the genocide committed against the Hutus claim to have been warned by some RPF soldiers. It is believed that RPF combatants alerted groups of refugees to flee because, according to them, their peers positioned behind them, at the time, had been ordered to eliminate civil populations.

There are many former RPF soldiers and officers across Europe who testify to have participated in these operations. For instance, it has been suggested that at some point it was necessary to use bulldozers, brought in from Uganda, to bury people in mass graves, in Rwanda.

One of them [former RPF soldier] went as far as to narrate that on one day his finger was swelling because he had it on his AK 47 trigger for an entire day. His targets, he says, were unarmed Hutu civilians. These events took place in the former province of Byumba, in the North-Eastern part of Rwanda.

The authors have been so little worried that the Internet has recently witnessed a proliferation of shows designed to glorify them. In these screenings, they openly brag about the crimes they committed against civilians. The latest of these is a documentary movie called « Inkotanyi » which was broadcasted in movie theatres.

A genocide of unbearable duration

The third characteristic is the length of its duration.

Recent History, that of the 20th century, has not known a genocide of such a long period of time.

The Mapping Report, cited above, examines the timeframe between 1993 and 2003 which suggests that 10 long years were sufficient to exterminate part of Hutu people of Rwanda and part of Congolese people who were also victims of the mineral wealth of their country.

Yet it is certain that this genocide began before 1993 in the Northern part of Rwanda and it remains quite difficult to determine with precision when it may have ended because there has not been any official military or political intervention to end it.

An effective genocide

The fourth characteristic, in this non exhaustive list, is the effectiveness of this genocide, which nevertheless has the largest number of direct survivors to date.

Indeed, this genocide was effective in the sense that it enabled the neo-colonial criminal enterprise to quickly reach its goal.

The Hutu population estimated at 6 million in Rwanda at the start of 1994, and who lived in their country, were involved in all levels of Rwanda’s public and private lives.

These people were not only evicted from their functions, they are simply not there anymore.

Many are in exile, others have been imprisoned, but their disappearance is mainly due to their systematic extermination, leaving behind a new but wounded generation.

This genocide has therefore proved to be effective on this aspect and it is not surprising that the current impunity only reassures the perpetrators as to the merits of the solution they implemented and that they are naturally determined to re-do if similar circumstances occurred in the future.

A genocide confronted with insidious denial

Coming now to its negation, this genocide knows the same mechanisms as the negation of all other genocides.

No one dares to deny the facts, meaning there was systematic extermination of part of the Hutu people in Rwanda and on the Democratic Republic of Congo territory by the RPF; targeting men, women and children without distinction.

This genocide therefore escapes the primary form of Holocaust denial, which is simply to deny the facts and claim that they did not happen.

However, the forms of denial to which this genocide is confronted are no less pernicious or less dangerous.

Minimising the number of the victims

The most common characteristic of all genocides is minimisation of the number of victims.

How many times have we not heard, for instance, that the number of Hutu victims might not exceed 500 000? As if that may actually not be enough.

It only takes one to look at the refugees camps that were located in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, in which refugees were meticulously counted by humanitarian organisations that came to their rescue in July 1994. It is believed that the day before these camps were destroyed by RPF attacks, they counted close to 2 800 000 refugees in October 1996.

In May 1997, the RPF government in Kigali proudly announced that it coerced some 500,000 refugees into returning to Rwanda while others were scattered in disarray in the dark forests of the Democratic Republic of Congo, between the Eastern Rwandan border and the Western Congo (Brazzaville) border.

Following these events, the number of refugees who survived and counted by the High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in Congo, early 1998, was estimated at about 400,000 people. This is the number that has and continues to be referred to which allows to evaluate the victims of the RPF who perished on the single territory of Congo, between 1996 and 1997, and the following years, at one million and a half people, if we consider the few survivors who made it to neighbouring countries.

Crime denaturation

Next comes the denaturation of crimes committed against Hutu victims which has become the most contemporary form of negation.

The crime of genocide is the most serious in international humanitarian law. Therefore, its denaturation only goes to diminish its gravity. It is in this sense that the genocide which Hutu people have suffered at the hands of the RPF is for example qualified as ‘exactions’. In other instances, this genocide is systemically watered down by calling it ‘selective massacres’ or ‘large-scale massacres’.

Today, evidence push some to at least qualify these crimes as ‘crimes against humanity’ avoiding the term genocide. Still, it is paramount to rightfully qualify a crime without changing its nature and to qualify its victims adequately, namely victims of genocide. It is also for this reason that generic expressions such as “Rwandan genocide”, “Rwandan tragedy” or “Rwandan drama” could indeed be considered inappropriate given the specificities of the genocide committed against the Hutus or the Tutsis.

If a genocide is committed in a broader context whereby other serious international crimes are committed, it is incorrect to bury it into a generic qualifier because that only brings confusion.

In other words, if the legal and judicial fact is that two genocides took place in Rwanda, one committed against the Hutu by the RPF between 1991 and 2003; the other committed against the Tutsi by Interahamwe militia (broadly speaking) between April and July 1994, referring to these events as “the Rwandan genocide” would in the end come to denying both genocides.

Victims demonization

Certainly, the demonization of victims remains the most abject form of genocide denial and is usually closely related to the denaturation of a crime.

From 1994, an unscrupulous media, probably funded by the perpetrators of this genocide, began to demonise the Hutu people in general by painting them as unsympathetic to the public. The climax of this narrative was reached in 1996, when a journalist wrote, for example, while the RPF destroyed Hutu refugee camps in Eastern Congo and exterminated men, women and children in the indulgent eyes of the world, that one should ask whether those children weren’t future genocidaire who might have inherited their parents’ ideology.

Quite strikingly, this journalist assumed that Hutus were ‘genocidaires’ as a people and that only moderate Hutus (dead or those who stayed in Rwanda) escaped that genocide ideology transmitted to children.

In fact, the expression “moderate Hutu’ contributed to the demonisation campaign against Hutus because it introduced the underlying idea that the Hutu people would be evil in essence but that a few would be moderate.

Considering that one can only be moderate in their opinion and not in who they are, the goal pursued by those who invented this expression and who continue to perpetuate it becomes clear. The practice of demonising a national or ethnic group by attributing certain crimes to them as a whole is nothing new. In fact, this practice is similar to the way Jewish people where collectively accused of killing Jesus Christ. Despite the absurdity of such accusations, some continue to entertain that in their spirit.

Once the victims are demonised, then the crimes committed against them become excusable or justifiable and lose their severity to generate reprisals or vengeance, if anyone still cares.

The most visible illustration of this are Rwanda’s death prisons and the famous gacaca courts whose function was first and foremost to purge Rwanda from Hutu men, starting from the educated, but which were presented as destined to punish the perpetrators of the Tutsi genocide, even though that too was secondary. In the same spirit and in continuity with gacaca courts was born the latest RPF government policy called “Ndi Umunyarwanda” (I am Rwandan). The Hutu young people targeted by that policy were massively called to apologise for the so-called crimes committed by their parents because they cannot be prosecuted for crimes committed before they were born.

Today, the RPF attempts to explain that it is fighting against genocide ideology which would have been transmitted to Hutu children, meaning those who denounce the genocide committed by the RPF against the Hutus.

The victims are therefore demonised and presented as criminals in a pernicious logic which consists in wanting to hide the reality of the genocide committed against the Hutus. This takes place through systemic brandishing of the fight against the denial of genocide against the Tutsis.

Placing a genocide in competition with another

This brings us to yet another form of negation which does exist for other genocides and not only for the genocide committed against the Hutus. This form of negation denies the crime of genocide by putting forward the existence of another concomitant crime/ prior crime which would justify that genocide.

We have all heard the expression ‘anti-genocide’ that some wanted to use in qualifying the genocide committed against the Hutus, after the one committed against the Tutsis, in an effort of absolution for the RPF -authors of the genocide against the Hutus.

This continues to be in the headlines because many people still struggle to recognize the existence of a genocide committed against the Hutus for the sole reason that there was a genocide committed against the Tutsis in Rwanda at the same time.

Worse, some innocent Rwandan youth openly wear negation T-shirts. Among the messages communicated through this venue, there is the idea that ‘there was only one genocide in Rwanda, the one committed against the Tutsis’ which suggests that there was no genocide committed against the Hutus.

It is fundamentally erroneous to deny a crime of genocide committed against another group based on the reason that a genocide was also committed against one’s own group as if it were about claiming a form of macabre exclusivity.

The genocide committed against the Hutus is distinct from the genocide committed against the Tutsis and one does not justify the other nor does it conceal it.

On the one hand, the genocide committed against the Tutsis, was committed by people who were generally identified as the Interahamwe. These crimes took place between April and July 1994 in areas that were officially controlled by the then transitional government of Rwanda.

On the other hand, the genocide against the Hutus, was committed over a very long period of time, that is, from end of January 1991 up to 2003 at least. It was carried out on wider territory covering the entire territory of Rwanda and part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (more specifically in the North-East and North-West regions).

And with this we have the transition toward one of the most incongruous form of denial regarding the genocide against the Hutus.

Mirrored genocide denial

The Hutu genocide denial campaign, which is led by its authors –RPF officers currently in Power, in Kigali, is essentially about silencing the people who fight for the recognition of the genocide perpetrated against the Hutus and justice for the victims.

The RPF does so by accusing them of denying the genocide against the Tutsi.

The people who fight for the recognition of the genocide against the Hutus are loosely labelled as «negationists» because they are also considered advocates of the “double genocide thesis”. Yet, logically, it is not he who claims the existence of a second genocide who is an alleged negationists. On the contrary, the negationist is he who, openly and in all impunity, rejects one of the genocides without any factual or legal argument.

The genocide against the Hutus is not the fruit of a thesis or the work of fanatics. It is a sad reality in which the supreme horror consists of continued bullying of the victims instead of seeking justice for them.

This campaign is evidently absurd and illogical, yet it has earned supporters in academia and political spaces in Europe even though at this time these are second level personalities.

In short, to openly engage in genocide denial by accusing the other of genocide denial is the world turned upside down. It is accusing the accuser.

So far, what is suggested here does not mean that there is no place for discussing legitimate negation or that one should unquestionably accept the genocide committed against the Hutus.

Everyone is free to demonstrate in what ways the elements of the crime of genocide may not be met in the specific case of the genocide against the Hutus. Indeed, every crime, independent of its category, requires a moral and a material element. That is, there must be both intent and act.

According to article 2 of the 1948 convention on the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide, the crime of genocide, against a national or ethnic group, requires ‘acts committed with the intent to destroy’. Yet that intent is not contested in this case. It is the result of facts and confessions made by those who committed these crimes, though they wrongly think that there was no genocide because their intention not to exterminate all Hutus but only a part of them.

The article continues and provides for what falls under acts of genocide. These include for instance, killing members of the group and/or deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part. It has been established that such acts were committed and that is the reason for claiming that a genocide against the Hutus of Rwanda was committed.

Since it is impossible to refute all the existing evidence with respect to this genocide, propaganda and the intimidation of victims took over. This strategy has been effective to the point that victims themselves deny the genocide committed against the Hutu people.

This genocide has the particularity of being denied by its victims. This type of denial is not the most successful illustration of the Stockholm syndrome. Rather, it is the consequence of continued impunity which pushed survivors to deny the crimes committed against them who are still under the authority of the perpetrators.

Genocide denial goes even further when some victims, now new members of the Kigali RPF , are coerced to publicly endorse the crimes committed by the RPF. In their official capacity, these victims engage in defences of RPF crimes and in doing so they endorse the crimes of which they were victims.

The current challenge is not even the recognition of this genocide by others but by Rwandans themselves, Hutus and Tutsis, starting with the Hutus who are the victims and who should be able to openly testify instead of giving in into fear.

Conditional recognition

How many times have we not heard people, in good faith, argue that if a tribunal were to qualify the crimes committed against the Hutus of genocide then one would have to accept it and face the evidence? But that is non-sensical because the existence and the qualification of a crime do not depend on judicial recognition. On the contrary, the fact that no tribunal has ever pursued these crimes is shameful for the entire humanity.

By Patrice Rudatinya MBONYUMUTWA.

www.jambonews.net

The author is a Rwandan born in 1975. He is a direct witness of the recent history of his country to which he developed a keen interest since his young age. He was in Rwanda on April, 06th 1994 and during the weeks that followed. He wishes to stress that this piece of writing is the result of 23 years of thinking and distance. During these years, he participated in numerous conferences, engaged with numerous Rwandan Hutus and Tutsis victims. He bought and read more than 230 books in addition to thousands of articles which comes to almost all that has been published on Rwanda after 1994 by different authors. He is a criminal defence lawyer who has also lectured at University.