In his book published in October 2019 by Éditions du Toucan, Rwanda: The Truth about Operation Turquoise, When the Archives Speak, Charles Onana takes the reader on a journey to uncover previously unseen documents, most of which were kept secret for decades in the archives of the Élysée, the Pentagon, and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR).

These documents include evidence that exonerates France and its army, softening the perception of their “heavy and overwhelming responsibility“[1] in the events that took place in Rwanda between 1990 and 1994. More notably, they include incriminating evidence against Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), highlighting its “questionable” role during the period of the genocide against the Tutsi, in which nearly a million innocent people were massacred.

Throughout the 662 pages, Charles Onana challenges certain widely held beliefs about the motivations of various parties, ultimately arguing that the French army never intended to support the genocidaires in their dark endeavours, that Paul Kagame’s RPF never aimed to protect the Tutsi from the genocide, and that there is no evidence of genocide planning by a so-called “Hutu regime“.

It is primarily for these last two points that six French associations[2] filed a complaint against Charles Onana on 20 October 2020, accusing him of genocide denial, on the grounds that his book was allegedly a “pretext to deny the existence of the genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda“.

The trial, which finally took place from 7 to 11 October 2024 in the 17th chamber of the Paris Criminal Court, focused on around twenty excerpts from the book; phrases, half-phrases, and some carefully dissected paragraphs in the light of the law penalising genocide denial.

What exactly is he being accused of?

According to the civil parties, the selected excerpts “materialise a denial of the crime of genocide […]” under French penal law, meaning each excerpt is alleged to match one of the types of genocide denial, similar to those seen in Holocaust denial cases. In fact, since there is no legal precedent in France addressing denial of the Rwandan genocide, the civil parties suggested the court refer to the extensive case law on Holocaust denial and apply it to the genocide against the Tutsi.

More specifically, Charles Onana is alleged to be guilty of (1) outright denial, (2) implicit denial, and (3) discrediting institutions. To persuade the judges, the civil parties isolated and commented on each excerpt to demonstrate its supposed “denialist” nature.

For example, concerning excerpt no. 4, deemed outright denial, where Charles Onana writes: “Continuing to go on about a hypothetical ‘genocide plan’ by the Hutu or a pseudo-rescue operation of the Tutsi by the RPF is a fraud, an imposture, and a falsification of history.” (page 460), the civil parties argue that the author “reduces the genocide committed against the Tutsi to […] a ‘fraud,’ an ‘imposture,’ a ‘falsification of history.'”

However, even a simple reading of this excerpt, even out of context, makes it unequivocally clear that Charles Onana is referring to the “genocide plan” mentioned by the RPF since 1994 as hypothetical, and not the “genocide” itself, which the author acknowledges as real in several other parts of the same book.

Similarly, for excerpt no. 3, also considered as outright denial, Charles Onana writes: “Paul Kagame and his men never saved the Tutsi from any ‘genocide,’ and they never intended to.” (page 456). The civil parties argue that the author “unequivocally claims that the Tutsi were in no way saved from a genocide,” whereas an objective reading of this excerpt shows that Charles Onana disputes the notion that Paul Kagame and his men saved the Tutsi, not the fact that the Tutsi were victims of genocide.

Finally, regarding excerpt no. 2, also regarded as outright denial, where Charles Onana writes: “This demonstrates, if it were still needed, that the conspiracy theory of a Hutu regime having planned a genocide in Rwanda is one of the greatest frauds of the 20th century.” (page 198), the civil parties argue that: “Mr Onana reduces the genocide committed against the Tutsi to a ‘conspiracy theory’ […]“.

However, during his statement at the end of the day on 11 October, Charles Onana insisted on reading the entire passage from which excerpt no. 2 was taken, allowing the court to see that the excerpt was actually the conclusion of a demonstration arguing that the theory of a “planned genocide” by a “Hutu regime” is a “fraud“, and not a denial of the genocide itself. Charles Onana reminded the court that he had reached this conclusion, noting that the RPF had led the world to believe they had proof of this planning but failed to present it, either to the ICTR or any other foreign jurisdiction judging the acts of genocide committed in Rwanda in 1994.

Surprising interpretations.

As for the excerpts classified as implicit denial, the civil parties’ interpretation is even more surprising.

For example, excerpt no. 15, deemed implicit denial, reads: “In Rwanda, Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa were savagely massacred.” (page 621). Strangely, the civil parties see this as an “implicit denial of the specificity of the massacres suffered solely by the Tutsi,” without specifying the appropriate way to refer to Hutu and Twa victims, as pointed out by Charles Onana’s lawyer, Emmanuel Pire, during the hearings.

Similarly, regarding excerpt no. 16, which states: “The aim [for the RPF] is to pass off their war of power conquest as a ‘war of liberation’ or as a ‘genocide of the Tutsi’ and, at the same time, to conceal the crimes against humanity committed by its movement, which are now very well documented.” (page 649); the civil parties claim this constitutes implicit denial by suggesting that the Tutsi sought “to instrumentalise a genocide to gain power […]“.

Once again, a dispassionate reading of this excerpt reveals that Charles Onana is referring specifically to the RPF, but the civil parties replace “the RPF” with “the Tutsi” as a whole. An astonishing, if not fallacious, extrapolation in the eyes of anyone familiar with the details of the Rwandan case.

Indeed, during his statement on the evening of Friday, 11 October, Charles Onana once again reminded the court that it is essential to distinguish between innocent Tutsi civilians, victims of the genocide, and the Tutsi rebels of the RPF, who committed serious violations of international humanitarian law, well documented.

For the remaining accusations, labelled “disqualification of institutions”, the civil parties criticise Charles Onana for his critiques of the ICTR’s work or that of French courts for their guilty verdicts. For example, in excerpt no. 18, he writes: “When the [ICTR] prosecutor struggled to provide evidence of both planning and genocide, he opted to use the artifice of ‘judicial notice’ rather than presenting concrete evidence.” (page 195).

Contradictorily, the civil parties view this critique as a form of “denialism,” even though they admitted in court that the ICTR was unable to provide evidence of this planning due to its mandate limited to incidents occurring between 1 January and 31 December 1994. This is the only observation on which the civil parties and Charles Onana may agree, with neither disputing that the ICTR Prosecutor failed to produce the evidence in question.

Regarding the claim that Charles Onana “systematically” placed quotation marks around the word “genocide,” the civil parties interpret this as “at least an implicit indication of denial […]“. However, the book contains over thirty passages where the term genocide appears without quotation marks.

Ironically, in their own complaint, the civil parties themselves used quotation marks around the word genocide over thirty times, without explaining how their quotation marks differed from those of Charles Onana.

In short, the twenty or so excerpts criticised by the civil parties appear to be more a matter of subjective, sometimes bad-faith, or even fallacious interpretation, as attested by the starkly opposing interpretations presented by witnesses on both sides.

Witnesses of Disproportionate Calibre

On his side, Charles Onana summoned a dozen witnesses whose expertise and credibility regarding the topics they testified on were indisputable. These included three senior officers from the French army, former Rwandan opponents of Habyarimana’s regime, current Rwandan opponents of Kagame’s regime, the former Belgian ambassador to Rwanda in 1994, a Rwandan human rights activist with 40 years of experience who has known both regimes, a former defence lawyer at the ICTR, and, notably, Belgian Colonel Luc Marchal, who commanded the UN peacekeepers stationed in Kigali in April 1994 and witnessed the events between the warring parties before, during, and after the genocide.

All of these witnesses, who had personally experienced the events of 1994 or worked with the ICTR, confirmed that Charles Onana’s book was not denialist in nature, with some even expressing unequivocal support for all of his conclusions.

On the side of the civil parties, the associations presented five witnesses against him, including Belgian lawyer Bernard Maingain, who also represents the Rwandan State and Paul Kagame in other cases, an American-Bosnian researcher with no prior connection to the Rwandan case, a French professor of public law, a young French historian, and Jean-François Dupaquier, a pro-RPF French journalist who, when questioned by the defence attorneys about recognising Hutu victims, chose to claim that ethnic groups did not exist in Rwanda rather than acknowledge the massacre of Hutu.

None of these civil party witnesses had personally experienced the events of 1994.

A Stark Double Standard

During their final pleas, the lawyers for three of the six associations clarified to the Court how the associations they represented were entirely independent from Paul Kagame’s regime.

For example, the lawyer for Survie explained at length that Survie should be considered objective, despite the fact that its founder, Jean Carbonare, had several contacts with Paul Kagame as early as 1993 and ended up collaborating with his regime after Kagame’s military victory in the summer of 1994[1].

This clarification was notable, especially as the other three associations—the Collectif pour les Parties Civiles du Rwanda (CPCR), IBUKA-France, and the Communauté Rwandaise de France (CRF)—made no such statement, which could imply that they are dependent on Kagame’s regime or, at the very least, accountable to it.

Conversely, the lawyer for FIDH explained that his client (FIDH) has not hesitated to denounce the current abuses and crimes of the Kigali regime. On this, Charles Onana personally responded by asking to see their press releases.

Onana also questioned what these associations have done in the case of Déo Mushayidi[4], a Tutsi genocide survivor with whom Onana co-authored The Secrets of the Rwandan Genocide, who has been imprisoned in Kigali for nearly 15 years for denouncing RPF crimes. He also highlighted the case of Kizito Mihigo[5], a famous gospel singer and fellow Tutsi genocide survivor, who allegedly “committed suicide” in Kigali prison in February 2020, a few years after releasing a song advocating genuine reconciliation and empathy for all victims, regardless of ethnicity.

Despite all this, the Prosecutor adopted the civil parties’ conclusions almost verbatim.

To Charles Onana’s surprise, she admitted that she had only read a few chapters of the book under prosecution yet upheld the civil parties’ interpretation, claiming the excerpts in question indeed constituted outright denials, implicit denials, or challenges to institutions as interpreted by Holocaust denial jurisprudence. As a result, she requested that Charles Onana be found guilty of genocide denial, without specifying a sentence, leaving it to the Tribunal to determine the appropriate outcome

A Historic Judgement

Beyond simply delivering a verdict of guilt or acquittal, the Tribunal will be deciding on much more.

The underlying reasoning in the judgement will be of particular interest to an informed audience, as it is expected to outline what should be considered “denialist” in France when discussing the responsibilities of various parties in the events in Rwanda in 1994.

For example, how will the Tribunal address the highly controversial issue of genocide planning, knowing that the position of the Paris Cour d’Assise is at odds with that of the ICTR regarding the existence of such a plan? Will mentioning that the ICTR failed to prove the existence of a genocide plan, which is a fact, be regarded as denialism in France?

What weight will the Tribunal give to the various testimonies from each side? Will the many witnesses who share Charles Onana’s perspective also be deemed “denialists”? And what of the credibility of witnesses who deny the existence of ethnic groups in Rwanda while simultaneously talking about a genocide against one of these “non-existent” groups?

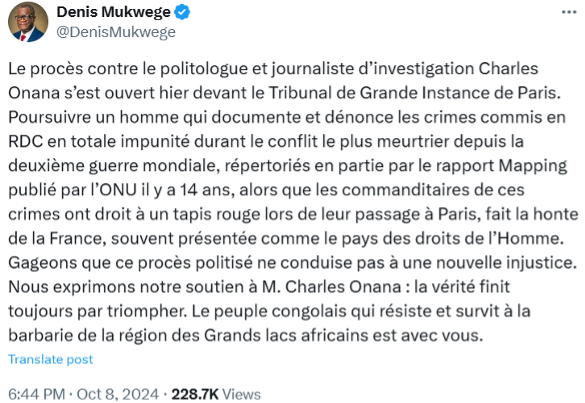

What will the Tribunal say about the geopolitical aspect raised repeatedly by Charles Onana as the primary reason for his appearance before the court? Indeed, during his address, Charles Onana explained at length that he was on trial due to his revelations about Paul Kagame’s expansionist aims in eastern Congo, a hypothesis widely shared by many Congolese, including Dr. Denis Mukwege, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who has publicly expressed support for Onana and labelled the proceedings a “Trial of Shame” for France.

How will the Tribunal handle the sensitive issue of Hutu and Twa victims? Is it truly “denialist” to state that Hutu and Twa were also massacred in 1994? Such a ruling would be unprecedented and would likely have diplomatic repercussions, as the UK and the US have repeatedly emphasised the importance of including all Rwandan victims in collective memory, as evidenced by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s tweet on April 7 of this year

Finally, the most important question: what about the crimes committed by Paul Kagame’s RPF? Will discussing these crimes, as Charles Onana has done, be deemed “denialist” in France? Will we see a judgement that orders the silencing of widely documented mass atrocities, crimes against humanity, or even genocide? Or will we see a judgement that allows survivors, victims’ families, researchers, journalists, and even magistrates to speak out about these crimes without risking accusations of “denialism”?

In short, there are numerous questions, and the answers, already anticipated as historic, may well shift how “denialism” of the Tutsi genocide is addressed in France from now on.

The eagerly awaited verdict is expected on 9 December 2024.

Brussels, November 11th, 2024

Gustave Mbonyumutwa

Former President of the Belgian association JAMBO ASBL, Gustave led the association’s efforts from 2017 to 2019 during the Belgian parliamentary debates that resulted in a law penalising, in Belgium, the denial of the Tutsi genocide. However, the law carefully avoided “restricting the ability of human rights organisations, journalists, and researchers to conduct their work without being unjustly labelled as denialists” [6].

[1] Survie, FIDH and LDH at first, Ibuka-France, CRF and CPCR in second phase

[2] According to the « Duclert » report, released on March, 26, 2021

[3] See letter from Rwandan President Pasteur BIZIMUNGU addressed to Jean CARBONARE on August 22, 1994

[4] https://www.amnesty.be/veux-agir/agir-individus/reseau-actions-urgentes/node/4990

[5] https://www.hrw.org/fr/news/2021/02/17/entretien-comment-une-chanson-scelle-le-sort-de-lartiste-rwandais-kizito-mihigo

[6] https://www.jamboasbl.com/article/observations-de-jambo-asbl-sur-le-nouvel-article-de-loi-tendant-reprimer-la-negation-des