Since their creation, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) have been at the center of heated controversies, especially regarding their classification as a “genocidal organization” by the Rwandan government. In an interview with the BBC on November 4, 2024, Rwanda’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Amb. Olivier Nduhungirehe, reaffirmed this stance, categorically stating: “The FDLR are responsible for the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi. There will never be any negotiations with a group that committed genocide.” Comparing the FDLR’s situation to that of Hitler’s regime in Europe, he insisted that no country would have agreed to negotiate with Nazi officials, adding: “It is impossible to negotiate with a genocidal group that killed more than a million people.”

These statements reflect Rwanda’s unwavering position against any dialogue with the FDLR. But are these accusations backed by solid, verifiable evidence? This article delves into this question by examining the facts and historical elements surrounding the FDLR to better understand their role in the broader security context of the Great Lakes region. Below is an analysis based on ten key questions.

1. Are the FDLR a Genocidal Movement?

The FDLR are often described as a genocidal movement due to their links with the former Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR). However, this affiliation remains the primary basis of this accusation, as no acts or documents to date demonstrate genocidal ideology within the FDLR.

A genocidal movement is an organization that plans and executes acts aimed at destroying an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), tasked with prosecuting those responsible for the 1994 genocide, convicted only a limited number of FAR officers, and none of the current leaders of the FDLR have been charged with genocide. Among the approximately 500 officers in the FAR before 1994, only nine were convicted by the ICTR. Some high-ranking FAR commanders, such as Brigadier General Gratien Kabiligi (Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations) and Major General Augustin Ndindiliyimana (Chief of Gendarmerie), were even acquitted by the tribunal.

Moreover, many former FAR members currently live freely in Rwanda, with some holding high-ranking positions within the Rwandan Defense Forces (RDF). These facts suggest that affiliation with the FAR alone does not define an individual or group as genocidal.

2. Why Integrate Former FAR Members into the Rwandan Government While Labeling the FDLR as Genocidal?

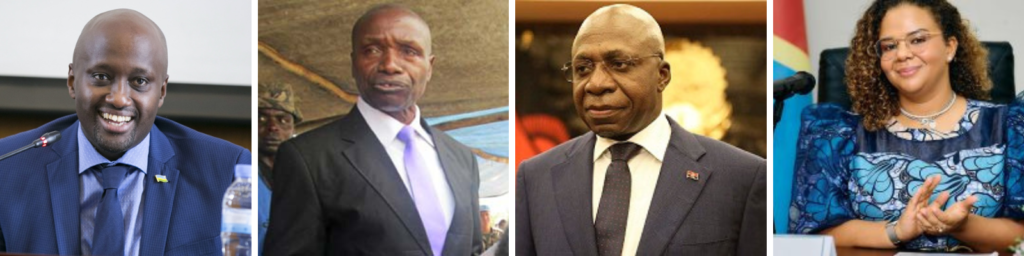

Since Paul Kagame became president, the key position of Minister of Defense has been held by five individuals, four of whom are former FAR members. These include Brigadier General Emmanuel Habyarimana, a former lieutenant colonel in the FAR before the genocide; Major General Albert Murasira, a former captain instructor at the Kigali Military Academy (ESM), who also worked in military administration under Habyarimana’s regime; and Colonel Juvenal Marizamunda, a former FAR lieutenant who went into exile in the DRC and Gabon before being forcibly repatriated to Rwanda. Upon his return, he held high-ranking positions in Rwanda’s security apparatus under Kagame’s regime.

General Marcel Gatsinzi provides another notable example. A senior officer in the FAR, he participated in a commission led by Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, which drafted a report titled “Definition and Identification of the Enemy.” This document was presented by the ICTR prosecutor as key evidence of a coordinated plan to exterminate the Tutsi civilian population, eliminate opposition members, and retain power. This report was used to support the existence of a genocidal plan, as it directly linked the Tutsi ethnicity with the concept of an enemy.

On the eve of the genocide, Gatsinzi was Deputy Chief of Staff of the FAR. Following the assassination of President Juvenal Habyarimana, Gatsinzi was appointed acting Chief of Staff of the FAR. According to the official narrative of the current Rwandan regime, this assassination was carried out by “Hutu extremists” seeking to take power and orchestrate genocide. Under this logic, Colonel Gatsinzi, who was promptly promoted to brigadier general, emerged as the primary beneficiary of the assassination by taking control of the army at a critical moment.

Despite this history, Gatsinzi was never sanctioned by the post-genocide regime and was instead rewarded with high government positions under Kagame, including Minister of Defense, while being promoted to the rank of four-star general—the first in Rwandan military history. This situation raises questions about the logic of labeling the FDLR as genocidal based solely on their links to the FAR. It highlights the fallacious nature of this argument frequently propagated by Kigali.

3. Does the Integration of Former FDLR Leaders into High-Level Rwandan Security Positions Contradict the Kagame Regime’s Stated Doctrine?

Paul Rwarakabije, a former commander-in-chief of the FDLR’s military wing, is a notable example. Before the FDLR’s creation, Rwarakabije was Chief of Staff of the Army for the Liberation of Rwanda (ALiR), the FDLR’s precursor. As such, he was a principal architect of the organization’s structure, doctrine, objectives, and strategy. Observers note that this organization’s objectives and directives have remained consistent since its foundation.

In 1994, Lieutenant Colonel Rwarakabije served as G3 in the gendarmerie’s staff, placing him in charge of operations. This role made him central to the institution’s actions. The Kagame regime regularly portrays the national gendarmerie of that era as a key organ of what it calls “the genocidal apparatus.” However, despite this affiliation and his later defection, Rwarakabije earned favor among Hutu refugees for his critical role in their protection in the DRC and northwestern Rwanda.

In November 2003, Major General Paul Rwarakabije orchestrated a dramatic surrender with 105 of his men, including much of the FDLR high command. His return to Rwanda was the result of six months of intense negotiations and persuasion by RDF Chief of Staff Brigadier General James Kabarebe. Before his return, Gacaca courts, established to prosecute alleged genocide perpetrators, had convicted over one million Hutus and listed Rwarakabije among the accused. Yet, upon his return, he was acquitted of all charges by Gacaca courts in the Kimuhurura sector and was granted official positions.

Since his integration, Rwarakabije has received privileged treatment from the regime, raising numerous questions. This leniency sharply contrasts with the treatment of other FDLR members, who are accused of perpetuating genocidal ideology. Furthermore, his family endured significant loss, as his wife and three of his four children were massacred by the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA) during the “Infiltrators’ War.”

Other former FDLR leaders have also assumed significant roles. Colonel Jérôme Ngendahimana, a former senior FDLR commander, was promoted to major general and led the RDF Reserve Force for several years. Lieutenant Colonel Evariste Murenzi, another former FDLR high commander, was promoted to brigadier general and now serves as Commissioner General of the Rwanda Correctional Service (RCS), overseeing all Rwandan prisons. These officers, some of whom conducted operations to reclaim Rwanda through armed means during the 1998 Infiltrators’ War, have been entrusted with prominent positions in Kigali’s administration.

These integrations raise a fundamental question: if the FDLR is truly a genocidal organization threatening Rwanda, why are some of their former leaders occupying strategic roles within the Rwandan government? This contradiction casts doubt on the sincerity of Kigali’s accusations against the FDLR and suggests an ambivalent relationship, oscillating between declared threat and pragmatic integration.

4. Did the FDLR Play a Role in the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda?

Formed in the year 2000—six years after the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi—the FDLR did not exist at the time of this tragedy. Over the past 30 years, although numerous reports from UN experts, international non-governmental organizations, and competent jurisdictions have been unfavorable to the group, none have established or documented mass crimes or genocidal acts committed by the FDLR since their creation. Considering this timeline, one might question how the FDLR could be associated with a genocide that occurred before their existence.

Since 2004, the UN Security Council has set up a group of experts tasked with producing biannual reports on the security situation in eastern DRC. These reports detail the activities of various armed groups operating in the region, including the FDLR. While the FDLR are regularly mentioned for involvement in security incidents, none of these reports have documented ethnic-based crimes committed by the FDLR.

This ongoing international scrutiny has not spared the FDLR but has also failed to reveal any elements suggesting a genocidal ideology underpinning their operations. It is thus critical to distinguish between crimes committed in a conflict setting and acts motivated by genocidal ideology. Although the accusation is frequently made, often fueled by popular perceptions or preconceived ideas, no concrete or verifiable evidence has, to date, demonstrated that the FDLR base their actions on a genocidal ideology.

5. Do the FDLR Use Terrorism to Influence or Destabilize the Region?

The designation of a “terrorist group” implies the systematic use of violence to instill fear and achieve political objectives. However, in 20 years, the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) have claimed responsibility for only one attack on Rwandan soil: in 2019, in Busasamana (Northwestern Rwanda), where a military barracks was targeted, resulting in the deaths of three soldiers from the Rwanda Defense Forces (RDF). In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), reports from the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office (UNJHRO) indicate that the FDLR are not among the most violent groups, unlike organizations such as the ADF, M23, and CODECO. Can they then reasonably be classified as a terrorist group?

In 2013, the United States placed the FDLR under the financial sanctions list of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, alongside M23, but without including them on the official “Foreign Terrorist Organizations” (FTO) list. This classification does not designate the FDLR as a terrorist group under U.S. standards, although they remain subject to economic restrictions.

The Army for the Liberation of Rwanda (ALiR), dissolved in 2000 to pave the way for the creation of the FDLR, is listed on the United States’ “Terrorist Exclusion List.” This designation is notably linked to the tragic attack on Western tourists in Bwindi National Park, Uganda, on March 1, 1999. During this incident, eight foreign tourists, including two Americans, were brutally killed.

However, serious doubts surround ALiR’s actual responsibility for this attack. According to Aloys Ruyenzi, a former Rwandan officer who defected, the operation was allegedly orchestrated by soldiers from the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) disguised as Interahamwe rebels. Ruyenzi stated: “The Western tourists killed in Bwindi National Park were victims of an operation planned by the RPF. The goal was to internationalize the threat of the Interahamwe and justify military operations in the DRC. By blaming these rebels, the RPF sought to bolster its image while eliminating foreign witnesses who could expose atrocities committed in areas under their control.”

Three Rwandans, Léonidas Bimenyimana, François Karake, and Grégoire Nyaminani, were accused of participating in the Bwindi attack and extradited by Rwandan authorities to the United States in 2003. Their trial, however, revealed troubling details: the defendants claimed they were tortured by Rwandan agents to extract confessions.

In 2006, U.S. Federal Judge Ellen Segal Huvelle ruled that the confessions obtained under torture were inadmissible. She stated: “The court is painfully aware that two innocent American tourists were brutally killed in Bwindi on March 1, 1999. However, the law cannot permit evidence obtained through coercion to be used in this courtroom.”

The judge also noted that the accusations primarily relied on these questionable confessions, describing the defendants’ detention conditions as inhumane and incompatible with fundamental principles of justice. The defendants testified that they had endured severe mistreatment, including “kwasa kwasa,” where their arms were bound in painful positions, as well as prolonged beatings.

It is worth noting that the FDLR, as a distinct organization from ALiR, has never been listed on the United States’ “Terrorist Exclusion List.” This case highlights the influence of Rwandan intelligence services in shaping the international perception of the FDLR.

As of 2024, the FDLR are not designated on any official list of terrorist groups, whether at the national, regional, international, or multilateral level.

6. What Justifies the Continued Existence of the FDLR?

The existence of the FDLR can be explained by a deeply rooted historical, political, and security context that has persisted for nearly three decades. This group was formed in 2000, following the massive exodus of over two million Rwandans, primarily Hutus, who fled their country after the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) seized power in 1994. While a significant portion of these refugees settled in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), others fled to different parts of the world. Some still live in refugee camps in Congo-Brazzaville, Uganda, or Southern Africa, while others have settled in Europe or the Americas.

This community has also endured chronic waves of massacres targeting refugee populations over the past 30 years, leading to significant loss of life. Another segment of the refugees returned to Rwanda, either voluntarily or under coercion, often in contested conditions. Today, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) officially recognizes over 240,000 Rwandan refugees. However, this figure significantly underrepresents reality; when including stateless individuals, unregistered refugees, and those living under false identities, the number easily doubles.

The FDLR justifies its existence by citing the lack of political dialogue with Kigali and the conditions that forced these refugees into exile: political repression, marginalization, and the absence of guarantees for a safe and dignified return. The Rwandan government has not established credible mechanisms to reintegrate these populations in a way that respects their fundamental rights. In this political vacuum, the FDLR positions itself, for some, as a tool for political advocacy and, for others, as a protective force.

The survival of the FDLR is also intrinsically tied to the chronic instability in eastern DRC, where insecurity compels every community to organize for its own survival. Composed primarily of young Hutu refugees, the FDLR provides a form of defense for populations that would otherwise remain unprotected. The 2010 UN Mapping Report documented the severe violence faced by these Hutu refugees in the DRC, with some acts potentially qualifying as genocide. These ongoing threats partially explain why the FDLR continues to exist.

Rebellions supported by Kigali, such as the CNDP, RCD-Goma, and the M23 (in both its earlier and current forms), have further exacerbated insecurity in the region. According to the most recent UN Group of Experts report on the DRC (June 2024), “the M23 and RDF specifically targeted areas predominantly inhabited by Hutus.” Such attacks reinforce the perception of the FDLR as a defensive force, even though they fall short of fully addressing the needs of these communities.

Additionally, the FDLR is not solely a military entity; it also includes a political organization and conducts social and community-based activities for refugees. Not all FDLR members are combatants—most are civilians, including women and children.

The existence of the FDLR reflects a failure to address a fundamental political problem. As long as the Rwandan government refuses to engage in dialogue with refugees and to address the root causes of their exile, the conditions enabling groups like the FDLR to persist will remain. A lasting solution requires regional and international efforts to establish inclusive dialogue, tackle the root causes of this crisis, and bring stability to the Great Lakes region.

7. Are the FDLR and M23 Comparable?

The M23, supported by significant Rwandan military aid, seeks to impose its dominance over territories in the DRC, controlling strategic areas and possessing heavy weaponry. In contrast, the FDLR, far smaller in number and capacity, have no territorial ambitions or comparable military support. Their primary goal remains the secure return of refugees to Rwanda. This comparison, often drawn in diplomatic discourse, obscures the fundamental differences between these two groups in terms of support, structure, and intent.

This tendency to draw a false equivalence between the FDLR and M23 recurs in international diplomacy. For instance, during his visit to Kigali in August 2022, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken stated that the FDLR benefited from DRC support, while the M23 received support from Rwanda. This formulation seems to assign equivalent responsibility to both countries, as if Rwanda’s active support for the M23 and the DRC’s occasional tolerance of the FDLR were comparable. However, this comparison, while politically convenient, is factually misleading.

According to UN estimates, the FDLR have between 1,500 and 2,000 members. In comparison, Rwanda’s military is unofficially estimated to have around 100,000 personnel, while the M23’s strength exceeds 6,000 soldiers. Today, the FDLR lack the material resources or human capacity to launch large-scale offensives against Rwanda. Their last significant attack on Rwanda occurred in 2001—over 23 years ago. In contrast, the M23, substantially supported by Rwanda, remains capable of mobilizing well-armed troops and exerting direct control over territories in the DRC, directly impacting local populations and causing widespread displacement.

Establishing an equivalence between the FDLR and M23 is not only erroneous but also potentially dangerous. In 2009, this false equivalence led the international community to encourage joint operations between the Congolese and Rwandan armies, such as “Umoja Wetu,” to combat the FDLR. These operations caused massive displacements and significant civilian casualties while exacerbating regional instability. Similarly, in 2013, similar pressures to “neutralize” the FDLR resulted in violent operations that severely affected civilians without addressing the conflict’s root causes.

This discourse also justifies Rwandan intervention in the DRC under the pretext of “securing” the region against the FDLR. However, as the UN Group of Experts observed, Rwandan military operations in the DRC often preceded recent phases of cooperation between the FARDC and the FDLR, suggesting the instrumentalization of the FDLR to justify broader actions.

In conclusion, the FDLR and M23 differ fundamentally in objectives, capacities, and impact on regional security. Drawing a hypothetical equivalence between the two to apportion responsibility between the governments involved is not only misleading but also risks intensifying tensions and prolonging the conflict.

8. Does the Rwandan Government Recycle Former FDLR Combatants for RDF and M23 Operations in the DRC?

The Rwandan Defense Forces (RDF) are regularly accused of supporting armed groups in eastern DRC, particularly the M23. According to the UN Group of Experts’ December 2023 report, approximately 250 former FDLR combatants reintegrated into Rwanda were mobilized by the RDF for tactical support and reconnaissance missions in the DRC, under the supervision of Rwandan military intelligence. The report states: “The RDF and M23 were supported by several tactical and reconnaissance teams comprising a total of 250 ex-FDLR combatants, operating under the command of Rwanda’s Defense Intelligence Directorate (DID).”

The case of General Côme Semugeshi illustrates this recycling strategy. A former gendarme and member of the Rwandan rebellion CNRD, he surrendered to MONUSCO in 2017 before being repatriated to Rwanda. According to a witness cited by RFI in the article “Rwandan Soldiers in the DRC: What Evidence?” (April 2020), Semugeshi, now integrated into the Rwandan army, was seen in 2019 alongside RDF personnel, deployed in Congolese uniform and participating in RDF operations.

This recycling highlights a significant paradox: while Rwanda labels the FDLR as a terrorist and genocidal group, it repurposes some of its former members by integrating them into its own armed forces, only to redeploy them in the DRC, thereby contributing to destabilization in the region. This instrumentalization of ex-FDLR members for Kigali’s military interests raises questions about the consistency and sincerity of Rwanda’s official position on the FDLR issue.

9. How Should the FDLR Be Classified?

The classification of the FDLR has been heavily influenced by the official narrative of the Kigali government, which consistently portrays them as a genocidal and terrorist group. However, the international community has rarely taken the necessary distance to analyze this narrative, too often adopting Rwanda’s discourse uncritically. This terminological choice is not trivial: it directly affects how the FDLR are perceived and treated while shaping the solutions proposed for peace in the region.

In diplomacy, words are carefully chosen, and the terminology used can either open up new possibilities or restrict available options. For example, in a February 2024 statement, the U.S. State Department referred to the FDLR as a “negative force” in the context of hostilities in eastern DRC—a markedly less aggressive designation. This lexical shift hinted at the possibility of considering solutions other than military intervention. Although this approach remains isolated and has yet to gain widespread consensus, it paves the way for a more constructive strategy, emphasizing dialogue.

Labeling a group as “terrorist” or “genocidal” tends to exclude any possibility of dialogue, favoring strictly military responses. However, in the case of the FDLR, this strategy has proven largely ineffective, failing to address the root causes of the conflict. In contrast, a more nuanced classification would allow for an examination of the movement’s political and social roots, thereby paving the way for a sustainable solution to the Rwandan refugees’ grievances.

It is therefore imperative to rethink this approach and adopt pragmatic terminology that fosters engagement and dialogue. The international community, particularly key actors involved in resolving the security crisis in eastern DRC, would benefit from considering the FDLR as a political resistance organization seeking to protect Hutu refugees in exile and negotiate their safe return to Rwanda, rather than treating them solely as a military group to be eliminated. By acknowledging the political dimension of the FDLR, we move closer to a comprehensive and lasting solution to their presence in the DRC, including their military component.

10. Why Could Dialogue with the FDLR Be Essential for Regional Peace?

The FDLR represent the primary voice of Rwandan refugees in eastern DRC, maintaining strong ties with over 250,000 refugees. Excluding them from the peace process would mean ignoring a key actor in resolving regional tensions. The peace process initiated in Luanda, which calls for the neutralization of the FDLR and the withdrawal of Rwandan troops from the DRC, could pave the way for constructive dialogue.

Over the years, several leaders have emphasized that dialogue with the FDLR could be essential for easing tensions in the Great Lakes region. In 2013, Didier Reynders, then Belgium’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, implicitly urged Kigali to consider this option, stating: “Dialogue with all forces often labeled as negative, if they lay down arms and agree to dialogue (…), is first a national priority, then a regional one.” Similarly, Tanzanian President Jakaya Kikwete, during a 2013 summit in Addis Ababa, invited Kigali to engage in negotiations with the FDLR, stressing that “there can be no lasting peace without comprehensive negotiations.”

In 2005, the FDLR demonstrated their willingness to dialogue by signing an agreement in Rome with the Congolese government, mediated by the Community of Sant’Egidio. In this declaration, they pledged to abandon armed struggle, explicitly condemned the 1994 genocide, and called for political solutions to regional conflicts. This step marked a significant milestone, constituting the FDLR’s first official acknowledgment of the genocide against the Tutsi—a meaningful move toward reconciliation.

However, despite these advances and calls for dialogue, Kigali continues to refuse any discussions with the FDLR while vigorously advocating for dialogue between the DRC and the M23, a group armed and supported by Rwanda. This inconsistent approach raises questions: why promote dialogue for external allied groups while denying it to internal opposition?

The Great Lakes region, deeply scarred by decades of violence and suffering, cannot afford to continue pursuing solely military solutions. Lasting peace can only be achieved through sincere negotiation efforts, as demonstrated by visionary leaders in the past. Engaging in dialogue between Rwanda and the FDLR offers a genuine opportunity to break the cycle of conflict and pave the way for long-term stability in the region.

Conclusion: Neutralization or Dialogue?

The FDLR represent a far more complex reality than the simplistic image of a purely genocidal group often portrayed. They are not merely an armed organization but also an expression of a vast population of Rwandan refugees, primarily in the DRC but also in neighboring countries such as Uganda and Congo-Brazzaville. These communities, comprising hundreds of thousands of individuals, view the FDLR as a means of defense against real or perceived threats.

Since their creation in 2000, the FDLR have continuously drawn volunteers from refugee communities and recent exiles. This dynamic underscores the deep connection between the movement and these populations. In the DRC, particularly in the North and South Kivu regions, the FDLR play a protective role for Hutu Congolese communities. This proximity has enabled the movement to establish deep roots and gain significant local support, especially in areas plagued by insecurity.

Despite numerous attempts at neutralization, including large-scale military campaigns such as Umoja Wetu, Kimia II, and Amani Leo, involving thousands of Rwandan and Congolese soldiers, the FDLR have shown remarkable resilience. They have survived the elimination of key leaders, such as Major General Sylvestre Mudacumura in 2019 and Colonel Protogène Ruvugayimikore, alias Ruhinda, in 2023. However, these losses have not led to their dismantlement.

What distinguishes the FDLR is their social base. The historical and community ties they maintain with Hutu Rwandan refugees and Congolese Hutu populations form the backbone of their resilience. These connections enable a constant renewal of their ranks and reinforce their perceived role as a bulwark against persistent threats.

The facts demonstrate that the military neutralization of the FDLR is ineffective in the long term. The movement derives its strength from its social and political roots, which cannot be eradicated by force. A pragmatic and sustainable approach requires recognizing the legitimate aspirations expressed by the FDLR and the populations they represent, particularly regarding security and the repatriation of Rwandan refugees.

To achieve lasting stability in the Great Lakes region, it is essential to move beyond exclusively military approaches and engage in sincere and inclusive dialogue. Addressing these demands is a critical step toward breaking the cycle of violence and opening a pathway to enduring peace.

Rwanda could play a central role in this transition by expanding its political space and facilitating the secure return of refugees under dignified and peaceful conditions. This would pave the way for transforming the FDLR into a political movement integrated into Rwanda’s political landscape, abandoning their politico-military structure.

In conclusion, achieving lasting stabilization in the Great Lakes region requires moving away from purely military solutions. A balanced approach, combining inclusive dialogue and acknowledgment of the conflict’s social and political dimensions, offers a chance to break the cycle of violence and usher in an era of lasting peace for all affected communities.

Norman Ishimwe

www.jambonews.net